In the Country of Memory: Jovanna Venegas Unveils Duality, Spirits, and Transformation in Conversation with Liz Hernández

En el país de la memoria, Installation view, pt.2 Gallery. Oakland, CA

Curator Jovanna Venegas and Liz Hernández engage in a dynamic exchange as they explore the depths of the duo exhibition "En el país de la memoria" (In the Country of Memory). The discussion delves into spiritual dimensions, the enigmatic presence of demons, the intricate theme of duality, and the yearning for an imaginary homeland. As Hernández unfolds her connection to artist Argelia Rebollo on these subjects, diverse materials used in the exhibition come to life, reflecting the essence of transformation and the passage of time. Hernández provides a glimpse into her artistic journey and the intentional material choices behind her approach, revealing a rich tapestry of concepts waiting to be unraveled.

JV: You have always brought on a spiritual component in your exhibitions: with the [SFMOMA] mural, you were calling for a higher power to heal our community. In Talismán, many symbols such as mirrors, eyes, and flowers called forth or perhaps represented aspects of the spiritual realm. Here, spirits, specters, or ghosts are even more present; we can hear and feel it with the sound of the typewriter in Es imposible regresar al país de la memoria (It is impossible to return to the country of memory); why do you think these spirits are getting louder? What is making them mark their presence even more?

LH: I’ve been interested in spirits and ghosts since I can remember. Mainly because they were often a part of my day-to-day life; my mom’s side of the family has always been involved with spirits through a specific kind of Spiritualist church we attended in Mexico. It was not uncommon to explain the world in terms of souls coexisting with us: good spirits, evil spirits, and spirits of people we know or those unknown to us. I grew up very Catholic, going to an all-girls Catholic school for most of my childhood, so engaging in the world of ghosts felt rebellious and subversive, but at the same time, going to the Spiritualist temple with my family offered me a lot of comfort and sense of belonging.

As to why these spirits are getting louder, it was triggered by how the world feels now. We are surrounded by grief and loss, which leads to many unknowns about the future. It makes me think about how Spiritualism developed in this country. Modern Spiritualism began in the mid-1800s in a small town in New York and quickly became popular during the Civil War because the list of men who died grew bigger and bigger. Many people turned to Spiritualist mediums, hoping to find answers to what happened to their loved ones or, at the very least, get proof that their soul was at peace. Similarly, now, I think many of us wish we had answers for a lot of despair around us: war, hate, sickness, and senseless acts of violence. We rarely find answers or solutions in our worldly realm, which might push some of us to seek answers in the spiritual world, whether through organized religion or the occult.

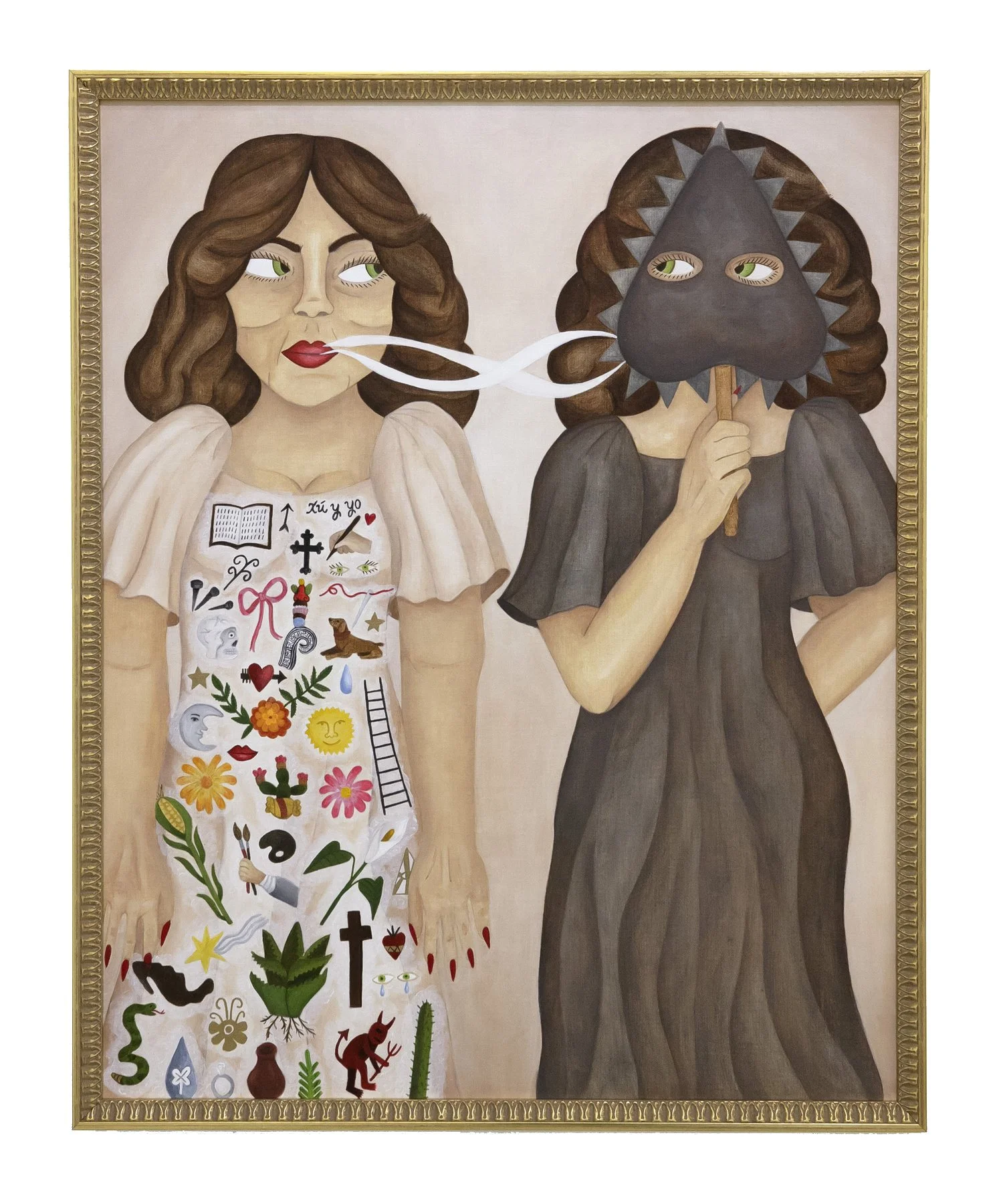

Argelia Rebollo "A José Emilio Pacheco, quien ha expresado todo aquello que desearía comunicar”

(To José Emilio Pacheco, who has conveyed everything I would like to communicate")

Acrylic on linen, Year unknown

JV: There also seems to be a recurring motif in the exhibition of demons, who are also supernatural forces, and depending on what culture and time, they serve different roles or are meant to deliver specific messages. In the work Confrontación, they are the most present and seem to be playing or torturing the figure; why do you think they are so present in this exhibition? What brought them out?

LH: In this show, demons represent intrusive thoughts that won’t leave you alone. They come out during periods of deep introspection when we put aside our day-to-day distractions and spend time with ourselves. Many people do not do that because it is often scary seeing what you find deep inside of you. I think about Argelia and how she was a recently arrived immigrant. Although she could speak English and had a comfortable life, she felt profoundly isolated and unable to express herself adequately, so she spent much time alone.

In Argelia’s work, she depicts the demons not as threats but as annoying beings, bugging her but never preventing her from going on with her day. I wish I could be like her and ignore intrusive thoughts that do not bring good. In my pieces depicting demons, I felt like, in contrast to Argelia’s, they often take over me and prevent me from living. The work that you describe, Confrontación, represents the first time you allow yourself to face your demons, the ugly side of you, which you’d rather ignore but is still you. After this moment of confrontation, one must face their demons and either control them, accept them, or banish them.

Liz Hernández "Confrontación (Confrontation)” Rust on aluminum, 2023

JV: They also seem to be rusted; why did they manifest in this material?

LH: A big goal for the exhibition was to make the invisible visible. I wanted to embody the process of evolution and transformation that happens when someone migrates. I keep going back to a quote in the gallery text written by Raúl Aguayo about Argelia’s work: “The act of migrating, beyond all its political weight, is rediscovering oneself in the world.” I thought of how rust reacts to the environment and time and how it becomes evidence of that transformation. Although rust is often considered a sign of decay, it eventually becomes a hard coating that protects the metal under it. To me, it was very poetic and described how I feel today.

Liz Hernández “Monumento a la mujer de las dos almas” (Monument to the Two-Soul Woman),

Low relief in cantera stone, 2023

JV: We can see a lot of doubles, pairs, or twins in the works; one shares while the other conceals, or in Monument to the Two-Soul Woman, it appears more as if they are plotting. This work makes me think of the divine twin brothers from Aztec mythology, Xolotl and Quetzalcoatl, who represent life and death or creation and destruction. I associate these works with duality and balance. We have talked about being immigrants in a place, how you often belong to two places while also belonging to neither, or how your Mexican version is different from your American version. What does this doubling mean for you?

LH: I wanted to showcase duality throughout the exhibition for many reasons. First, because it is a show of two people, Argelia and I, and we share the feeling of being split between the place we want to be and the one we inhabit. Between past and present, between what is near us and what happens in that place where we are not.

When I first moved to the US in 2011, I never anticipated staying, so I initially kept a low profile, mainly focusing on school. I didn’t have a phone for two years because I was convinced I would return home soon. Even now, I lack an official state ID. This unexpected reality of staying has led me to have an identity crisis. Argelia, too, faced a similar situation, leaving her comfortable life in Mexico to join her husband in California in the mid-1950s. This upheaval marked both a rupture but also the beginning of her art practice. I relate to her story so much.

The doubling also illustrates how I coexist with different versions of myself. I engage with California Liz Hernández, who can talk about the works so eloquently; in a sense, she is my spokesperson. I know Mexico Liz Hernández starts tearing up as she thinks about what is present in the exhibition because it is so close to herself, so I have come to terms with the fact that they need to collaborate. That’s particularly true for the stone piece you mentioned. The figures aren’t suspicious of each other but embrace and realize that working together can create something beautiful. The symbol between the two figures is a glyph from the Codex Borbonicus that represents “in xochitl in cuicatl,” or song and flower, which the ancient Nahua people used to depict the concept of poetry.

Argelia Rebollo, “El encuentro de las dos Argelias” (The Meeting of the Two Argelias)

Acrylic on linen, Year unknown

JV: There is also an important reference in The Meeting of the Two Argelias with The Two Fridas, by Frida Kahlo, who did the work during a period of loss, particularly from her divorce from Diego Rivera, but also struggling with her identity and sense of place. Do you think Argelia had seen this work and was responding to it? And if so, why?

LH: I’m glad you brought this up because I hadn’t noticed. I’m not a big fan of Frida Kahlo, so I completely missed this reference. Argelia could have seen the painting, considering they were both alive around the same era. The similarities between the paintings are remarkable. However, it could also be that they both were going through a similar situation, an identity crisis, which often leads to thinking about yourself as a fragmented person due to grief and loss. I wish we had more of a clear timeline to compare when the piece was made or if Argelia left some writing about Kahlo’s work; however, it’s hard to know. With Argelia’s work, we can only play these guessing games.

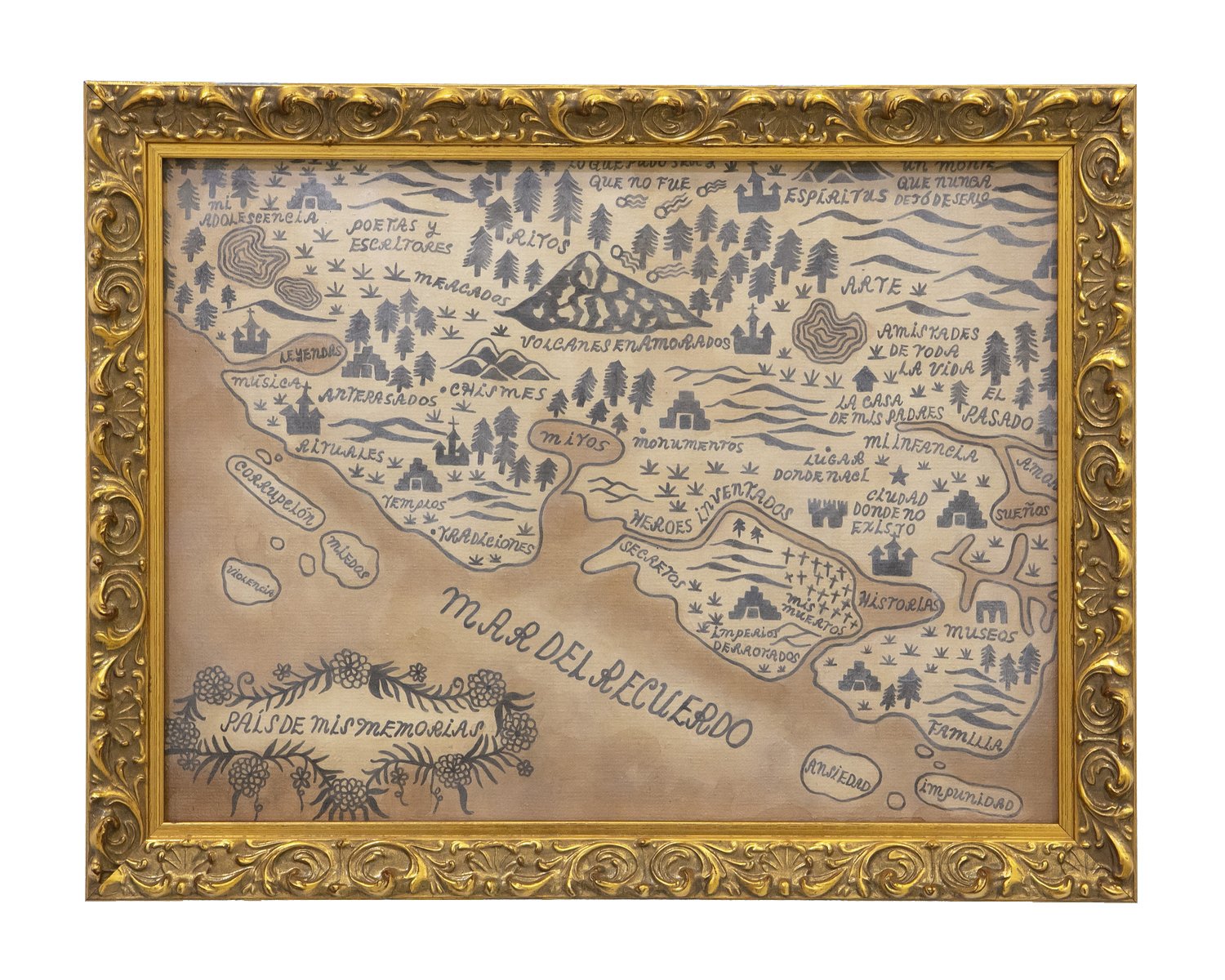

JV: Other themes under the exhibition's surface are ideas around place, land, and country, or perhaps a longing for an imaginary country. Because often, we fantasize about the place we leave behind, but in reality, we know we cannot really return to it. Can you talk about this sentiment of longing and some of the creative decisions you made to approach it or manifest it visually?

LH: The idea of the country of memory, the fantasy country, or the idealized country was inspired by conversations with you and our friend Fernanda Partida Ochoa. In two different instances, you both told me that my idea about living in Mexico was a fantasy, mainly because I saw it through the eyes of nostalgia. At first, hearing that hurt because the truth hurts, but it also offered me some peace.

Then, reading Argelia’s writing about her idea of “the country of memory” was a critical moment for me. She expanded on the belief that one doesn’t have to love a state but all the things that make up a country, which made me feel good. It is hard to feel love for the Mexico of the 100,000 missing people, the Mexico that doesn’t treat femicide with the urgent attention it needs, the Mexico of corruption and impunity. Still, it is so easy to love the celebrations, the places where you feel happy, the food, the landscape, the culture, our family… We might think that this place will welcome us with open arms, no matter what, which is never guaranteed.

This realization allowed me to understand the country of memory as a place within me that I can access once in a while when I get sad or homesick. We cannot go back to the past as much as we wish, and I often spend way too much time there.

Argelia Rebollo, “Mapa del país de la memoria: territorio perdido” (Map of the country of memory: Lost territory),

Acrylic on Linen, Year unknown

Regarding creative decisions, I selected materials that allude to time. Stone feels eternal, rust shows the passage of time, a typewriter is a marker of antiquity, and Argelia’s paintings are framed in a way that embodies a different era. I wanted to manifest time because getting older has deepened these feelings around my homeland and because it is a timeless, universal topic: people have been migrating for centuries and will continue to do so.

I also kept wondering about what tangible things make up an “official country” and how Argelia gave it a territory with its shape, name, and landmarks. I wondered what else the country of memory needed and thought of monuments. That led me to question what a monument represents, and I ended up thinking about how most of them contain very nationalist narratives that impose a discourse on the population in Mexico. I did not want to recreate that, so I created two images the inhabitant of the country of memory would consider important based on Argelia’s works and writing: The woman of the two souls and the souvenir of the place where I don't exist. A souvenir is evidence that we visited a different place or country. It is as if I wanted to ensure there was proof that this place was real. I used Cantera stone because it is a material that is widely used in monuments in Mexico; to me, it feels governmental.

En el país de la memoria, installation view, pt.2 Gallery, Oakland, CA

JV: You studied industrial design and started to work as an artist after you graduated, so in some ways, you are a self-taught artist, which, to me, can often free an artist from a lot of pre-conceived notions about materials and processes that you get in art school. But in each exhibition, you painstakingly approach and go deeply into a new material. In the last exhibition here, you took Nahuatl classes and made highly detailed embroidered works. And now we see these rusted materials, paintings, and the introduction of Arduinos and live components. What draws you to a new material? How do you approach it when it is entirely new to you? What prompted the choices and experimentations you followed here?

LH: At first, not having a formal fine arts education made me feel like a fraud, but as time passed, I fully embraced the fact that my experience was unique and that you can turn your difference into your strength.

I incorporate new materials because I love learning and believe each material has a distinct language. I acknowledge that sometimes I want to express an idea that painting simply cannot do, but metal or stone will. Or that as much as I draw a ghost typewriter, it is more impactful if we feel a presence typing in the room.

My art practice has strong connections to craft techniques. I am a collector of objects from all over Mexico, and I love the diverse array of materials used and how they tell the story of a group of people, as well as their location and belief systems. I highly respect the commitment of craftspeople to mastering their materials, which inspires me to become an expert at the techniques I develop. My connection to craft does not mean I am against new technologies; that is why I wanted to incorporate Arduino into my ghost typewriter. I am very excited about it, and I plan to continue using microcontrollers to evoke specters or create environments that come to life.

Sometimes, I worry this works against me, as this approach may not align with the art world's preference for repetition. However, I resist conforming to such norms because the exploration of materials is integral to my practice. You can expect my material library to continue growing—I can't stick to the same thing over and over; it gets boring!